|

|

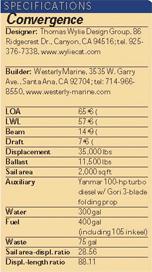

The mission was to create a true sailor’s boat for a family that had recently spent time cruising in a powerboat and didn’t want to give up what they liked about that—having a room with a view and steering from inside on rainy days. The mission leader was West Marine’s founder, Randy Repass. Repass wasn’t interested in having “just” a boat. Because his heart and his pocketbook belong to the world of water, he is happy to simply say, “I think our sport needs new ideas.” “I bought a powerboat because 70 percent of West Marine customers own powerboats, and I needed the education,” Repass says. “Also, we wanted to cruise the Pacific Northwest, where it rains a lot and you don’t always have a sailing breeze. The boat, a 42-footer, was a lobsterman type, and it served us well for nine years. There were nasty days when we’d cross paths with a sailboat, and we’d be sitting inside with the heater running, watching the world go by, while over on the sailboat everybody was hunkered below decks out of sight except for one poor guy stuck on deck in the rain in his foulies. That made an impression on both of us.” Randy and his wife, Sally-Christine, have always wanted a yacht they could cruise with their son, now age nine, around the world. But first they had to get to the starting point. “Putting a boat together has been a lot of hard work,” Repass says, “even for me.” Repass began what was to become West Marine in his garage in the tucked-away town of Watsonville, California. Many years later he saw a boat named Jade, owned by a Northern California sailor and drawn by a Northern California naval architect named Tom Wylie. Jade is 68 feet long overall and has a well-proportioned pilothouse, and that was what first brought Repass to Wylie’s door. What followed could make even a cynic believe in fate. Tom Wylie likes unstayed cat rigs. They just make sense to him, and some of the most knowledgeable sailors in his area have been converted to Wylie-designed performance hulls with unstayed cat rigs and wishbone booms. But Wylie is also a dreamer, and when Repass first appeared he had already made a wild-haired commitment to build a large cat-ketch on speculation. The ketch would serve as an eco-friendly alternative ocean research vessel, or an alternative school ship, or both. Think of the movie line, “If you build it, they will come.” The name of the boat would honor Derek M. Baylis, racer, designer, engineer, and grand old man of Northern California sailing. Repass was intrigued with what he saw. He and Sally-Christine had already considered most known builders of long-distance cruisers without finding what they wanted, but this design was surprisingly different. To Repass, parts of Wylie’s boat looked as if somebody had been reading his mind. But he didn’t rush in. Wylie recalls, “Randy took a close look at the Baylis project, but it took him nine months of coming around and asking a lot of questions before he finally made a decision. Then, as quickly as I can tell you about it, he told me that I was going to design his boat, Westerly Marine was going to build it, and he also wanted to become involved in the Baylis project.” Repass says now, “The thought emerged that we could try out ideas on the Baylis, and it would be launched in time for us to learn from it.” However, reality played out differently. Convergence was well along before the Baylis was launched. It was a synergistic relationship nonetheless. Wylie recalls that, “Randy colored a lot of aspects of the design for the Baylis, but never as a businessman, always as a sailor. He likes fresh ideas—his house is off-grid, for example—and he believes that form follows function in a boat.” The hull is a sandwich of E-glass and West System epoxy over Core-Cell foam; a Kevlar lining has been added to the outer skin to ensure integrity in a collision. Three watertight bulkheads guard against catastrophic flooding. The decks are carbon fiber with a balsa core. Although the carbon structure added $10,000 to the cost, the resulting weight savings lowered the center of gravity. Repass considers that to be a good investment. Extra bulkheads reinforce the hull at the mounting position for the fin keel, which carries a lead ballast bulb. The spade rudder is also built extra strong, so even a hard grounding shouldn’t prove a problem.

On deck

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Forty-watt solar panels make the yacht energy independent |

The pilothouse comes a close second to the rig as the boat’s most striking feature. It combines a saloon, galley, and nav/steering station and is larger than the cabin the family knew and liked in their lobsterboat.

Repass says, “When you put a big house on a sailboat you have to solve three problems. First, how do you make it look good? Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but I think we succeeded here. Second, how do you see over it? We dealt with that by raising levels in the cockpit. Third, can the windows break? We’ve used glass that is hurricane-rated. In tests it has withstood the impact of a two-by-four traveling at 35 miles per hour. What it takes to achieve that is a layer of PVB (plastic) laminated between two layers of heat-strengthened glass at a total thickness of 7/16 inch. That’s twice as thick as a car window.”

The pilothouse roof provides more than shelter. Fitted with 20 of Solara Energy’s 40-watt solar panels, the surface is designed to produce enough electricity to run the boat without other charging sources. These high-output silicon-wafer panels are good for 22 amps at 24 volts for a theoretical total of 3,000 watt hours per day, assuming 5 to 6 hours of sunshine. Solara’s panels conform to the roof ’s curvature and can stand up to foot traffic.

Belowdecks

|

||||

| The nav station at the forward end of the pilothouse has plenty of room and great visibility Peter | ||||

|

|

The interior styling is varnished cherry, with traditional-style white trim. Cherry countertops have been used in the galley and heads “because they hold up well, and they look great,” Repass says. The plywood sole is faced with individual cherry-veneer planks with relieved edges interlaid with 3⁄4-inch strips of anti-skid.

Nothing in the pilothouse blocks the view to the outside, whether you are cooking in the galley, resting in the dinette across from the galley, working at the nav station, or just kicking back on the 4-foot-long forward-facing helmsman’s bench. Moving forward you step down to cabin level, where there are three staterooms and two heads. At the aft end of the pilothouse you step down into another sleeping cabin nestled alongside the engine compartment and a world of accessible storage and comsystems space.

One advantage of a pilothouse is the space available beneath it. On this yacht there is a generous pantry area that will serve well when stocking for along cruise. There is also a washer/dryer, fuel and water tankage, and easy access to all equipment. The adjoining engine room space has 6-foot headroom, a sink for washing up, a 7-foot workbench running fore and aft, and ports to ventilate it. A hatch to the cockpit increases ventilation and serves as an emergency exit. There is also four-sided access to the 100-horsepower Yanmar turbo diesel that drives the yacht at 11 knots with a three-blade Gori propeller.

The yacht uses a 24-volt system, and gel-cell batteries are installed because they do not produce flammable hydrogen when being charged, are maintenance-free, and can be fully recharged without losing capacity. The battery bank is oversized because the family wants to be able to ride at anchor for days without running the diesel.

Under sail

Repass recalls that before he finally decided to built Convergence, he talked to everyone he could about the merits of unstayed cat rigs and nobody had anything bad to say at a practical level. “Yes, they do look different,” he says,“ but once you get past that, they open new horizons. Engineers stopped using wires to support airplane wings a long time ago. Yes the rig moves around, and that takes some getting used to. But having no wires helps us have a skinny design, and skinny designs are fast.”

Convergence has two free-standing tapered masts that carry full-batten sails and wishbone booms. The carbon-fiber masts and booms were heat- and pressure-cured in an autoclave for high strength and low weight. Because the spars are designed to flex progressively toward the tips, they can spill air in puffs, and that, the designer says, provides a smoother ride by not transferring sudden stresses to the deck.

Because the masts flex so much, modern brittle sail laminates are not appropriate. Repass and Santa Cruz sail maker David Hodges worked with Challenge Sailcloth to develop a new woven Spectra/Dacron radial fabric that is 100 pounds lighter than an all-Dacron mainsail.

Almost everyone who sails with Repass is struck by the irony of his making a living selling boat stuff while owning a yacht that is rigged for simplicity. There are, for example, only four winches on this 66-footer. Repass answers simply that what really counts here is the quest for better and happier sailing.

In early trials the yacht hit 13.5 knots running downwind wing-and-wing in a 20-knot breeze. With the right conditions it should easily surpass 20 knots downwind under full control. While the motorboat cross-pollination might suggest that some sailing qualities have been compromised, that’s simply not the case. On every point of sail the helm of Convergence has a precise feel; she “talks” to the driver the way a good yacht should. She feels alive.

One stormy day on San Francisco Bay last spring, not long after the yacht had been launched, Repass was steering Convergence on port tack and sighting forward over the top of the pilothouse. Everything was fine for a while, but then the heavens opened and the rains came down. So the three people aboard did the obvious. They moved the party inside and kept right on sailing, listening contentedly, perhaps even smugly, to the pitter patter of rain on the roof.

|

|||

|

|

||